“It’s the ultimate joy of the journey, rather than the satisfaction of the destination” – that fuels most successful road trips; the search for adventure on the road and the never quite knowing what’s going to be around the next corner.

1. Transfagarasan Road

Romania: Heart of Darkness

Measured by chills down the spine, the twists and drops of Romania’s Transfãgarasan Road pack a more fearsome punch than the Transylvanian Alps’ most famous former resident, Vlad III the Impaler, the Walachian prince who inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula. “You see crucifixes on the side of the road, and you dread to think what [the driver] must have gone through—it’s a sheer drop,” says Paul White, a British expat living in the nearby countryside who writes a blog called Wild Transylvania.

Winding north-south between Romania’s two top peaks and reaching more than a mile high, the Transfagarasan follows the Arges River, skirts the crescent-shaped rim of Vidraru Dam, and visits the banks of the emerald Vidraru Lake. Along the two-lane road (speed limit: 25 miles an hour), drivers cross 27 bridges and aqueducts and navigate an unlit, half-mile-long tunnel—as well as around shepherds and their flocks holding up traffic. Tourists stop at the ruins of 700-year-old Poenari Castle, Dracula’s onetime home atop some 1,480 stairs in the Arefu commune.

Backstory: High in the Fagaras Mountains of the southern Carpathians (another name for the Transylvanian Alps), the road was built in the 1970s as a strategic 100-mile military route.

Inside track: Often treacherous weather conditions mean the road is reliably open only from late June through mid-October; during cold months, the road becomes inaccessible beyond the Bâlea waterfall, a 20-story chain of cascades. From there, a red cable car whisks travelers to Bâlea Lake, with two year-round chalets and an ice hotel built from scratch each winter.

2. Blue Ridge Parkway

Virginia-North Carolina: Tangled Up in Blue

Spanning two states and 469 miles without a single stop sign or traffic light, the winding Blue Ridge Parkway unspools along ridgetops, into fertile valleys, and past the highest peak east of the Mississippi (Mount Mitchell) as it links Waynesboro, Virginia, in the Shenandoah Mountains to Cherokee, North Carolina, in the Great Smoky Mountains. “If your bladder could hold out and you have enough gas, you could drive the entire length of it without ever stopping,” says Dan Brown, a retired superintendent of the popular parkway.

Of course, farms, fields, and small towns offer plenty of diversions worth braking for, and most people linger longer than one day. They climb Sharp Top Mountain in Virginia, as Thomas Jefferson once did, eat cornmeal cakes at the historic Mabry Mill, or wander beneath the white oaks, red maples, mountain magnolias, black cherries, and tulip poplars at Flat Top Manor, gorging themselves on bluegrass music and Americana.

Backstory: The ridge’s name comes from the soft blue haze that seems to wrap the mountains from a distance.

Inside track: Famous for the high drama of its fall foliage, the route inspires no less awe the rest of the year, insists Brown—from spring’s blooming blankets of wild ginger, trout lily, and jack-in-the-pulpit wildflowers and budding trees to the summer’s “plush southern Appalachian landscape” of verdant green, as well as the “bleak,” beautiful winter.

3. Grossglockner High Alpine Road

Austria: Vertical Playground

Classic BMWs and roadsters zoom around 36 curves—which climb nearly 3,000 feet to a dizzying 8,215-foot vantage in just under 30 miles—on the Grossglockner High Alpine Road between the Austrian states of Salzburg and Carinthia. Overhead, griffon vultures and golden eagles circle the Alpine peaks, where rare ibex and chamois roughhouse and pudgy marmots scurry among resurgent populations of brown bears and wolves.

“If you have blue sky, it’s just out of this world,” says Johannes P. Hofer, an Austrian native who has lived in New York for decades but returns to Zell am See each year. “There’s never a visit when I don’t go up on this road”—if he can arrange it, behind the steering wheel of a borrowed convertible. The icing on top (other than the actual glacial glaze)? The joyride delivers drivers to the wilds of Hohe Tauern National Park, the largest nature reserve in the Alps and a magnet for hikers, cyclists, and snowshoers.

Backstory: Named for the 12,460-foot Grossglockner, highest in the Austrian Alps, the serpentine road was completed in 1935 and built on the traces of bridle paths and ancient Celtic and Roman trails.

Inside track: The Grossglockner charges a toll (around $43). Between May and November, the road accesses the Kaiser-Franz-Josefs-Höhe visitors center, where a funicular shuttles passengers to an overlook of the colossal Pasterze Glacier.

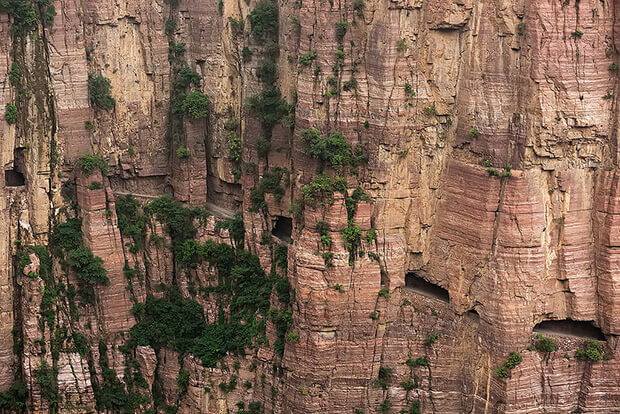

4. Guoliang Tunnel Road

China: Mission Impossible

In 1972, after centuries of isolation, the villagers of Guoliang decided to forge their own route to the outside world. Deep in the Taihang Mountains in northeastern China, they had long relied on a steep mountain trail sometimes referred to as a “heaven ladder.” Then 12 local men hand-carved a rough recess through the mountain. The Guoliang Tunnel Road (officially known as the Precipice Long Corridor) is that marvel of human will. To drive through the corridor requires a similar level of resolve. Tucked away in a remote corner of the country, west of Beijing, the passageway is hard to find. But those who have made the journey describe it as an exceptional sight. Just 19 feet wide and 13 feet high, the twisting tunnel has rough, open “windows” peering out from the cliff’s smooth rock face and down hundreds of feet to the gorge below.

Backstory: According to a plaque at its entrance, the nearly mile-long tunnel took six years to dig, the only tools being eight-pound hammers and steel drill rods.

Inside track: “While I traversed the tunnel, I had an uneasy feeling it might collapse,” says Darren Crawford, a traveler from Nottingham, England. The rock walls are badly cracked, with chicken wire at the entrance. Drivers are wise to turn on their headlights and honk their horns as they pass through.

5. Historic Columbia River Highway

Oregon: A Wrinkle in Time

Long ago bypassed by an interstate, the skinny two-lane Historic Columbia River Highway, poised on the side of the Columbia River Gorge, has seen little change since it was completed in 1922. Traveling from one small Oregon town (Corbett) to another (Dodson) a mere 15 miles away, the road’s most popular remaining portion takes in six state parks, seven waterfalls, and, on clear days, views of five mountain peaks, including the explosive Mount St. Helens. “To take that old highway is like stepping back in time,” says Darren White, a local fine-art photographer. During the silver thaw of winter, its famous waterfalls freeze and icicles as thick as tree branches hang from the highway’s graceful arched bridges. Spring and early summer pop with blooming endemic wildflowers—including the fuchsia-and-yellow poet’s shooting star and white-petaled Columbia Gorge daisy, and the Oregon ash and cottonwood trees grow dense with green. In the fall, the road slips under a fiery awning of oranges, reds, and yellows.

Backstory: The first planned scenic byway in the U.S. follows strict design protocols (for example, no grades steeper than 5 percent) inspired by Switzerland’s 19th-century Axenstrasse byway.

Inside track: At Crown Point, drivers stop at the Vista House, an elegant art nouveau observatory 733 feet above the Columbia River. Samuel Lancaster, the Multnomah County engineer who oversaw the highway’s development, said that from this perch the river “could be viewed in silent communion with the infinite.”

6. Atlas Mountain Road

Morocco: Magic Carpet Ride

Like a Formula 1 circuit without the safety checks, Morocco’s Atlas Mountain Road tests drivers’ mettle. Carved into the spine of northwest Africa, the 117-mile route can take several hours, with two narrow and guardrail-free lanes snaking around too many blind curves to count. “You go whooshing around 200- or 250-degree turns,” says David Wisner, a former teacher in Tangier. Here the grand prize is the otherworldly landscape seen from the Tizi-n’Tichka Pass as the road climbs more than 6,000 feet from ancient Marrakech, over the High Atlas Mountains, then back down to the desert oasis of Ouarzazate (the “Hollywood of the Maghreb,” the filming location for Lawrence of Arabia a half century ago). Along the way, obstacles range from unpredictable surface conditions to goats, camels, and mules blocking the road.

Backstory: The French Foreign Legion constructed this byway in 1936 on the path that explorer turned priest Charles de Foucauld documented in the 1880s.

Inside track: Telouet, the decaying capital of what was French Southern Morocco, features the once grand casbah of T’hami el Glaoui, who ruled the region in the early 20th century.

7. Milford Road

New Zealand: Need for Speed

The southwest corner of New Zealand’s South Island poses the best kind of driver’s dilemma: Wide-open roads, most famously the Milford Road (aka Highway 94), beg for velocity but also demand constant rubbernecking. From Queenstown, on Lake Wakatipu, a circuitous journey on state highways proves a worthy prelude to the glacier-carved Milford Sound. Like a drumroll, the final 75 miles on 94 travel through rain forests, around the perpetually white-capped Ailsa mountains, along the shores of Lake Te Anau, to the mirror-like, tea-colored water of the fjord. There, 150 or so residents live among a marine reserve for penguins, dolphins, and New Zealand fur seals. But for all the region’s eye-widening allure, it’s hard not to let your inner drag racer out to play. Exceeding the speed limit (62 miles an hour) is tempting, says Melissa Antonelli, a Seattleite who lived in New Zealand and learned so firsthand. It was “just me and the mountains and a beautiful running river,” says Antonelli of the largely unpopulated rural Fiordland region. “Then the cops came and gave me a speeding ticket, and I thought, ‘Where were you? There’s nobody else around.’?”

Backstory: Rudyard Kipling once described Milford Sound as the “eighth wonder of the world.” The Maori named it for the piopio, a native bird that’s now extinct.

Inside track: The Milford Road eventually meets the Avenue of the Disappearing Mountain, where an optical illusion makes the peak appear to shrink as people approach it. Drivers stop at Lake Gunn for a short nature loop.

8. North Yungas Road

Bolivia: Driving by a Thread

For some 65 miles in the Bolivian highlands, little more than a lane separates drivers from skydivers. North Yungas Road, including a 25-mile pass marked with memorial crosses known as the Death Road, leads from the outskirts of La Paz—the world’s highest capital—to the small town of Coroico. A nearby paved bypass completed in recent years provides a safer alternative, but mountain bikers and others who dare to take the old Death Road begin their white-knuckled adventure through the pass of La Cumbre on a barren 15,255-foot ridge. Glimpses across the valley offer vivid reminders of their precarious position up a vertical wall. Finally, the path descends into a humidity-choked haze of enormous palm fronds and wild coca bushes, teeming insects, and farms cultivating coffee and citrus.

Backstory: In the mid-1990s, the unprotected precipice earned notoriety as the most dangerous road in the world.

Inside track: “It’s extremely narrow,” says Dan Grec, a Canadian traveler who recently road-tripped from Alaska to Argentina. “There are plenty of places where, if you came across an oncoming car, you would have to reverse and figure out how far back to go until you could fit past each other.”

9. Icefields Parkway

Canada: Where the Wild Things Are

On the 144-mile Icefields Parkway, connecting Banff and Jasper National Parks, the quiet of the Canadian Rockies runs as deep as the region’s many glacier-fed lakes. Yet loneliness scarcely stands a chance. Here, titans of the Great White North—from bighorn sheep, caribou, and moose to grizzlies and black bears—embody the beasts of childhood fantasies; then, every so often, into the scene waltzes a creature looking straight out of a Dr. Seuss book. Local tour agent Mirit Poznansky drives the highway regularly, but a recent, rare sighting of the shy Canadian lynx, a wild cat with peculiar pointed tufts on its ears, stopped her in her tracks. The dreamscape is full of those pinch-me moments, perhaps none more surreal than the crystalline inverted landscapes reflected in the parkway’s lakes, each famous for having a distinctive hue, such as the turquoise of Bow Lake and the emerald of Lake Louise.

Backstory: Built during the Great Depression, the byway opened in 1940 as a single lane of gravel, upgraded in later decades. At roughly the halfway point, a massive expanse of interconnected glaciers called the Columbia Icefield sits on a triple divide. Its snowmelt feeds into the Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic Oceans.

Inside track: “The only time you get a traffic jam is if there’s a bear on the side of the road,” says Poznansky. “We call those bear jams.”

10. Trans-Andean Highway

Chile-Argentina: Dangerous Curves Ahead

The Trans-Andean Highway delivers more thrills than a theme park, coiling along 226 miles of mountain passes between the booming Chilean capital of Santiago and Mendoza wine country in the foothills of western Argentina. A defunct railway tracing part of the route only adds to the roller-coaster effect. As one of the major thoroughfares of the continent’s Southern Cone, the road is as seductive to sightseers as it is crucial to commerce, with semitrailers as well as international buses gunning it up 29 rapid-fire switchbacks that climb to some 11,500 feet on the Chilean side of the Andes.

At Christ the Redeemer International Pass—named for a four-ton statue placed there in 1904—a nearly two-mile-long tunnel cuts through the rugged mountains to a border crossing notorious for long lines and multihour delays. The tunnel also signals a striking divide. “In one trip, you have two totally separate ecosystems,” says U.S. expat Cary Gilbert, who manages a Mendoza restaurant. On the Argentine side, “it’s desert, with beautiful rock formations in all different colors. Then you come out the Chilean side, and everything’s green.”

Backstory: Locals call the crawl through the Andes the Paso de los Caracoles—“snails’ pass.”

Inside track: From the Argentine side of the tunnel, drivers can glimpse four-mile-high Mount Aconcagua, the tallest peak in the Western Hemisphere.

Source: National Geographic